Joan of Arc as Fairy Saint (?)

(A fair warning, reader, that it is not often that I allow myself so much leisure and freedom in the public expounding of my UPG - academia will do that to you: not always citing one’s sources at any given point in an argument becomes unthinkable, no one creates or thinks in a vacuum. Particularly where it concerns what might be controversial stances and takes, I aim to be mindful of the words I choose, of the influence they bear. But I am not here to argue, and wish only to reconcile - to share my perspective, my practices in filigree, watermark here to take you with me on a journey through what was a discovery that changed my outlook on things I thought I knew. Note that, though documented, though substantiated to an extent, the conclusions below are very much my own.)

The Knight of Chastity

“Hath loosd her helmet from her lofty hed (…)

Which whenas they beheld, they smiteen were

With great amazement of so wondrous sight

And each on other, and they all on her

Stood gazing.”

— Lewis Spenser, The Faerie Queene, III. IX. 23 (1590)

(About the female knight Britomart, Knight of Chastity, and the effect produced on a crowd of men by the sudden revelation of her gender and beauty, upon taking off her helmet.)

There are few feminine figures, historical and otherwise, who exert on me such a long lived and long standing fascination as St Joan of Arc, and, needless to say, I am certainly not the only one to be quite taken by her, regardless of one’s faith, origins and beliefs - so much so, that I am not even sure Joan’s story is deserving of an introduction anymore. All know of the divine calling of a humble peasant girl from Lorraine, of the way she took up arms against the English, pledged allegiance to an exiled king, and secured crucial victory on the battlefield. All know of her capture, of the pretence of trial at the hands of her enemies, where cross-dressing was a leading charge, and relapsed heresy a death warrant. All know, of course, of the fire - of the ashes carried away by the French rivers.

Ditto, Joan of Arc is the patron saint of France - and what a patron Saint to have, frankly: the simple mention of her name, conjuring up vivid imagery, vibrant story arcs and legends and tales and songs. Joan of Arc: the myth, made of fantastical depictions of a powerful, virginal woman-warrior kneeling or horse-riding, clad in armour, raising banner and sword against the English invader, her brow held high and defiant even in the face of the pyre. A “Knight of Chastity” herself, she is claimed left and right still, a free spirit, guided by mysterious Voices, haunted by Visions, touched by something Other, in a way that radically separated her from the common people and proclaimed a fate both exceptional and dramatic, a fate so dire and true - extraordinary, yet terrible. Joan of Arc, of the unburnt heart - carrying an undying flame within.

I stood gazing.

Yet… as someone who renounced my baptism many years ago, who declined this very faith and religious fervour that guided Joan of Arc on her own journey in order to cultivate other relationships, I believed Joan was, so to speak, properly off-limits - a saint and spirit I could recognize the existence of, and admire abidingly from safe distance, but a saint - meaning a being who was, despite obvious connexions with what I tend to be drawn to in this world and the other, altogether forbidden to me.

… Or so I thought - that is, until recently. For, you see, last summer an idea - no, not even that - an intuition, a knowing, a nudging, a tugging… something, small and probing, started to germ within me, and soon, it grew - root system stemming, more and more, until it emerged as yet unverified, in a bold question:

What if Joan of Arc saw fairies ?

I could not tell you, exactly, where this embryonic idea came from initially - I know that, at the time, my preoccupation was merely intellectual, my curiosity, detached, purely theoretical, because I assumed little weight would be contained in this statement - Joan is, undeniably, of a Catholic confession. In my heart, the truth was that I had started on my own journey of seeking pathways of reconciliation and avenues between my adoptive and birth lineages. I harbour a certain sadness (hiraeth) for my birth town which is home less than before, as opposed to where I currently live in the world. Is there a word for regretting the absence of mountains - the movement in their stillness ? With the obtention of my British nationality has come an even deeper sense of tear - something only an expat can know about intimately: the pride of doing well for oneself in foreign lands, mixed with the quiet deliquescence of feeling like one belongs, fully belongs, to where one was born, no longer - or less.

Hence, as I missed France, I clung to my idea - did Joan of Arc saw fairies ? did she, really ? - with a fierce mind, this progeny I embraced and nurtured - and, like a coal piece or ember stoked, it started to warm me, blazing. In it, I found more substance than I could have ever imagined and hoped for.

This was troubling.

I compiled books, articles, records, sources primary, secondary, and tertiary. I spoke to friends, consulted colleagues and talked with peers to compare UPG, studies, conclusions. I practiced and listened, I visited and heard, I interpreted and was taught. There are many amongst the ones reading this article, that I need to thank. I shared my research and was led to be shared with in turn, in ways that deepened and expanded my own narrow understanding of things.

Did Joan of Arc saw fairies ? is not a straightforward question to answer. It is seductive, and there is a case for it, one that we will discuss below, but it is not so easy nor simple. The lore of Fairy; you see, is sparse and few in France, not as vivid as in the Isles, save for Britanny. It is extremely territorial, extremely topographical, localized, hidden, shrouded in namesakes and fortifications, extremely specific, extremely preserved through oral means - and not as much in historical records. It is complicated to parse through, closely entwined with Marian cults and the lore of sacred wells, springs and fountains, stars, bridges, caves and

trees.

The Maiden of Oakwood

The legend of Joan of Arc preceded her birth by far, and carried on long after her death. She is undoubtedly a Catholic saint, but when she was first martyred, it was by the Church. She is special in that there was a time where she was explicitly difficult for the religious authorities of her faith to wrap their heads around, an ambiguous figure whose very in-betweenness was a problem. No less than two trials were needed for the Church to make up its mind about what to do of Joan. Saint or martyr, hero or villain, prophet or madwomen, man or woman, England or France… Joan is liminal, and thus inherently polarizing.

The Church had a long list of charges brought against Joan, but none are more striking than the accusations explicitly porting over her relationship with fairies throughout her adolescence.

… the Maid would come forth from the oakwood, and work miracles…

… the young Maid “from the borders of Lorraine”, the Maid who would save France…

… France - ruined by a woman, restored by another…

… an armed woman who was to save the kingdom.

“I am not afraid, I was born to do this.”

It starts like all good epic stories. You have, of course, heard about the prophecy. Have you ? Have you heard of the prophecy - the one which foretold the coming of the wondrous Maid ? Which prophecy - who said it - was it Merlin ? St Bede the Venerable ? Euglide of Hungary ? Marie d’Avignon ? The one which spoke of the maid of oakwood ? The one which spoke of the maid who would save France ? Is that not the same one that said that France, once lost by a woman, would be restored by another ? Is there another one ? Who spoke, first, of the armour - of the sword, of the battles, of the pyre ?

In her own words, told to the King, the way Joan saw it was thus:

“Four things are laid upon me:

to drive out the English;

to bring you to be crowned and anointed at Reims;

to rescue the Duke of Orléans from the hands of the English;

and to raise the siege of Orléans.”

— William Trask (trans.), Joan of Arc: In Her Own Words (1996)

But how did Joan know ?

Who told Joan what she was meant to do ?

(What if Joan of Arc saw fairies ?)

The inceptions are nothing short of irreal, spectacular : here we have a peasant girl (a nobody), hearing voices in a very pastoral decor in countryside France where fairy folklore, as it happens, abounds, and is very strong, and is, in fact, known to Joan - that much we know from the trials. Joan, we know, was aware even of the prophecies spoken about her.

Joan knew many things.

“Jeanne in her youth was not taught or instructed in the belief and principles of the faith, but was lessoned and initiated by certain old women in the use of spells, divinations, and other superstitious works or magic arts. Many inhabitants of these villages are known from olden times to have practiced these evil arts, and from certain of them, and especially from her godmother, Jeanne declares she has often heard talk of visions or apparitions of fairies or fairy spirits, and from others also she has been taught and filled with these evil and pernicious errors about the spirits, so much so that she confessed to you, in judgment, that until this day she knew not whether these fairies were evil spirits.”

— W. P. Barrett (trans.), The Trial of Joan of Arc (1932)

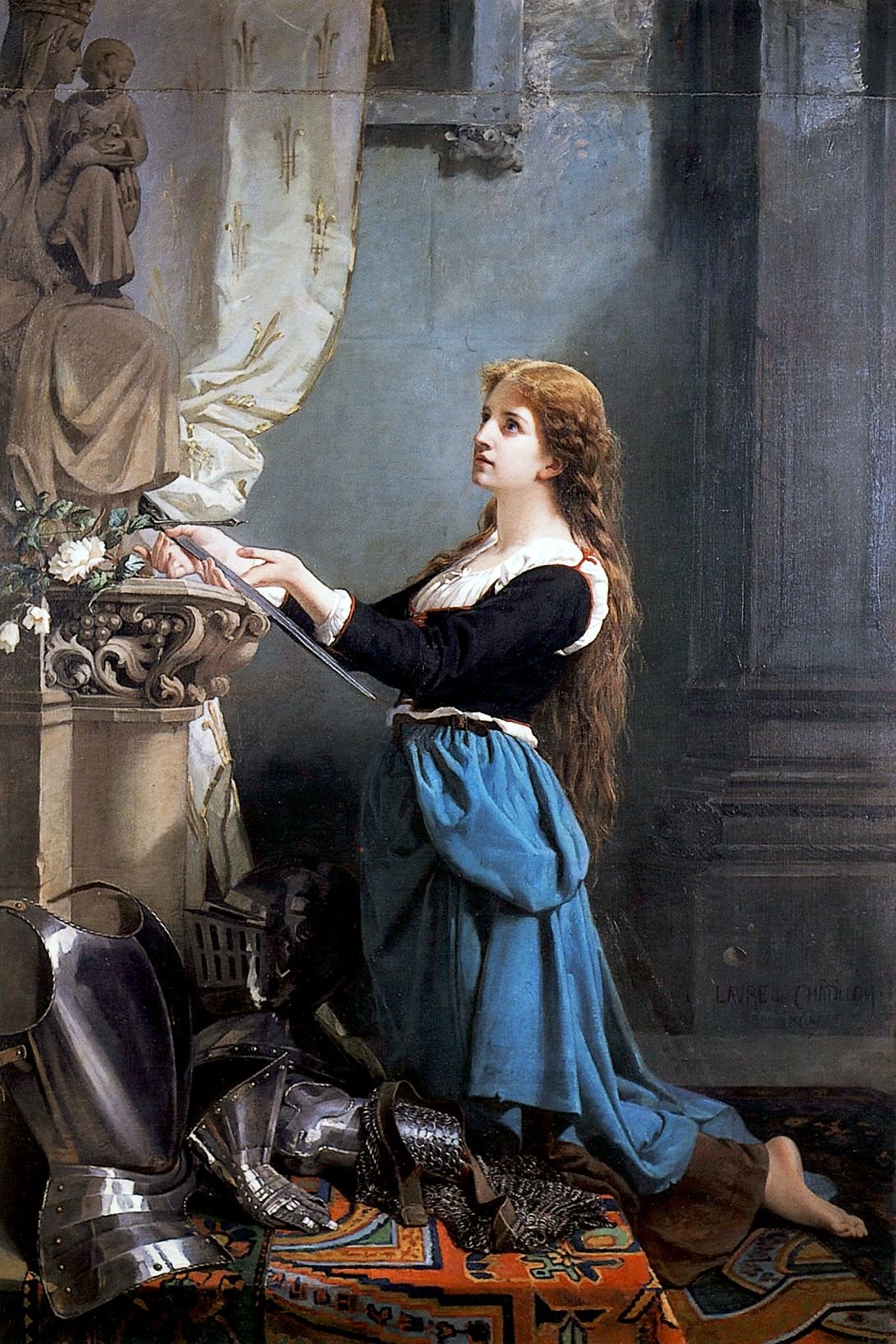

Joan had visions.

Joan heard voices - charms and songs, runes of poetry and prophecy: the very essence of Fairy.

L’Arbre-Fée de Bourlemont (The Bourlemont Fairy-Tree)

“Près de la maison de Jeanne d'Arc, un sentier montait, à travers des touffes de groseilliers, vers le sommet du coteau ; la crête boisée se nommait le Bois Chesnu. A mi-côte, jaillissait, sous un grand hêtre isolé, une fontaine, objet d'un culte traditionnel. Les malades tourmentés de la fièvre venaient, de temps immémorial, chercher leur guérison dans ces eaux pures... Des êtres mystérieux, antérieurs chez nous au christianisme, et que nos paysans n'ont jamais consenti à confondre avec les esprits infernaux de la légende chrétienne, les génies des eaux, des pierres et des bois, les dames faées hantaient le hêtre séculaire et la claire fontaine. Le hêtre s'appelait le Beau Mai. Au retour du printemps, sous l'arbre de mai, “beau comme les lis”, les jeunes filles venaient danser et suspendre aux rameaux, en l'honneur des fées, des guirlandes qui disparaissaient, disait-on, pendant la nuit.”

—H. Martin, Histoire de France, 1833

In the Bois Chesnu (literally, “Oak Wood”), Domrémy (department of Lorraine), France, stands a tree.

The tree is not an oak (or is it ?) - the tree is, some say, a beech (and some others, a hawthorn). Tall, with silvery bark, it is shadowing a spring of shining water, a fountain or well that is said to possess miraculous properties, gathering the sick, the old, the barren. France is replete with such topographical milestones, probably inherited from pre-Christian / neolithic beliefs, common to all the so-called Celtic lands - healing springs and holy wells, fountains sacred to one ̶g̶o̶d̶(̶d̶e̶s̶s̶)̶ saint or another, important to pilgrimage and baptismal water alike, pinnacles of water blessings and rituals.

The tree, or beech, or oak (or hawthorn), was known amongst the local to be enchanted : it was called Arbre-Fée (Fairy Tree), Arbre-aux-Fées (Fairies’ Tree), or then again Arbre-aux-Dames (Ladies’ Tree).

The “dames”, in French, is a respectful euphemism found commonly to designate the Pale Ones, which are more often than not thought of as female beings. French folklore does not harshly discriminate between fairy spirits and nature spirits, land spirits, and spirits of a particular place. The “dames” are often described clad in white, beautiful, shining. The fées or faes or fayes of France are like the fairies you may know - caught, theurgically speaking, between heaven and earth, other-than-human and more-than-human - certainly, capable of harm as well as love, of cruelty as well as kindness. To the Catholic Church of fifteenth century France, fairies have no soul to save, for They lack one to begin with, and as thus, like animals and the beasts of the untamed nature (Their realm - deep lakes, profound forests), They are, of course,

not to be trusted.

Hauviette, a friend of Joan and wife of Gerard of Syonne, near Neufchâteau, remembers the Ladies’ Tree of her childhood, and describes it vividly:

“There was a tree in the neighbourhood that, from ancient days, had been called the Ladies' Tree. It was said formerly that ladies, called Fairies, came under this tree; but I never heard any one say they had been seen there. The young people of the village were accustomed to go to this tree, taking food with them, and to the Well of the Thorn on the Sunday of 'Laetare Jerusalem’, called the Sunday of the Wells. I often went there with Jeanne, who was my friend, and with other young girls on the said Sunday of the Wells. We ate there, ran about, and played. Also, we took nuts to this tree and well.”

— W. P. Barrett (trans.), The Trial of Joan of Arc (1932)

(What if Joan of Arc saw fairies ?)

What does it mean to see fairies, in 1431 rural France ? It means that if you saw ladies by the Ladies’ Tree, you saw ladies by the Ladies’ Tree. Your heart had an answer for you, the judges, another. For who could say that one’s beliefs are not always informed, filtered, refined in the crucible of one’s education, through one’s own cultural understanding ? In Joan’s village, the priest would help you understand the world around you, and there is little in the way of small, innocent propitiations to a tree or a river than a peasant girl of the time would not innocently syncretize to the word of the priest, in good faith. It is thus my opinion that, as is apparent in Joan’s trial records, a “fairy faith” cultus was indeed still rendered to the tree and fountain in Domrémy when she lived there, and that in all too known a story across Celtic lands, this cult was overlaid with the broader Christianisation of France - there, not quite. Hidden. Keltoi. There is, worth mentioning, a long history in France of conflation between more or less local Fairy Queen(s), and the Holy Mother / Blessed Virgin (similar iconography, white ladies honoured at Lourdes, strange vierges noires / black virgins appearing, etc.).

What is a maid to know about saints ? What is a maid to know about fairies ? More than about saints, likely, but then again - how is one to know for sure ?

Questioned about the tree, Joan recounts:

“She answered that, fairly near Domrémy, there was a certain tree called the Ladies’ Tree, and others called it the Fairies’ Tree; and nearby is a fountain. And she has heard that people sick of the fever drink of this fountain and seek its water to restore their health; that, she has seen herself; but she does not know whether they are cured or not. She said she has heard that the sick, when they can rise, go to the tree and walk about it. It is a big tree, a beech, from which they get the fair May, in French le beau may; and it belongs, it is said, to Pierre de Bourlemont, knight. She said sometimes she would go playing with the other young girls, making garlands for Our Lady of Domrémy there; and often she had heard the old folk say (not those of her family) that the fairies frequented it.”

— Words attributed to Philibert, Lord Bishop of Coutances, ibid.

But Joan’s judges are pressing, and the fairy tree is not their sole concern.

Was Joan taught about the fairies ? Whom by ?

Did Joan consort with the fairies ? How so ?

And, crucially: are fairies evil spirits, Joan ? Should you have listened to Them ?

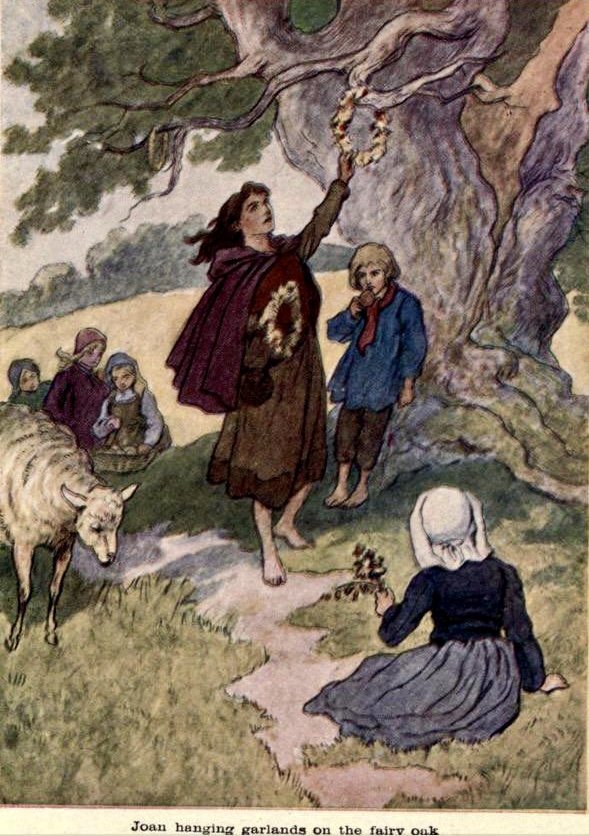

On Saturday, the 24th of February, she said that (…) she has heard Jeanne, the wife of mayor Aubrey of Domrémy, her godmother, say that she had seen the fairies, but she herself does not know if it is true. She never, as far as she knew, saw the fairies, and she does not know if she saw any elsewhere. She has seen the maidens putting chaplets of flowers on the boughs of the tree, and she herself has hung them with the others, sometimes carrying them away, sometimes leaving them there. She adds that ever since she knew she must come to France she had taken little part in games or dancing, as little as possible. She does not know whether she has danced near the tree since she had grown to understanding; and though on occasions she may well have danced there with the children, she more often sang than danced there.

On Saturday, March 17th, asked if her godmother who saw the fairies is accounted a wise woman, she answered that she is held and accounted a good honest woman, and not a witch or sorceress. The same day, asked if she had not heretofore believed the fairies to be evil spirits, she answered that she did not know. And the same day, when asked if she knew anything of those who consort with the fairies, she answered that she never went and never knew aught of that, but she had heard that some went on Thursdays. (…)

(…) The said Jeanne was wont to frequent the fountain and the tree, mostly at night, sometimes during the day; particularly, so as to be alone, at hours when in church the divine office was being celebrated. When dancing she would turn around the tree and the fountain, then would hang on the boughs garlands of different herbs and flowers, made by her own hand, dancing and singing the while, before and after, certain songs and verses and invocations, spells and evil arts. And the next morning the chaplets of flowers would no longer be found there.”

— W. P. Barrett (trans.), The Trial of Joan of Arc (1932)

These excerpts, which are important in that they contain direct quotations of Joan’s own words, leave space for Joan’s voice to be heard, and allow us to infer three things:

That the knowledge of fairies was still common where Joan was from, and that she was told about it from an early age.

That, during her childhood, Joan actively participated and innocently engaged, with other children, in semi-pagan / definitely non-Christian rituals of propitiation to the fairy tree and fountain of Domrémy, weaving garlands of flowers, offering them to “what was dwelling there” along with songs and dances.

That, upon hitting puberty, “what was dwelling at the tree and fountain” spoke to Joan - and that Joan not only heard, but, in turn, listened, and answered.

From these records it seems also clear that the Church suspected, or feared (assuming the trial was done in good faith), a lineage of fairy seership in Joan’s family and friend relationships. Striking, indeed, is Joan’s description of her own godmother’s abilities, her evident reluctance to blame or accuse her, even when she must have known herself in great danger. Striking, also, is Joan’s equal refusal to condemn fairies as demons, her rebuttal in casting them as evil and wicked in the way of the Church - a heretical stance, in which her interrogators try, and succeed, to catch her with leading questions.

Who spoke to you, Joan ? Who did you answer to ?

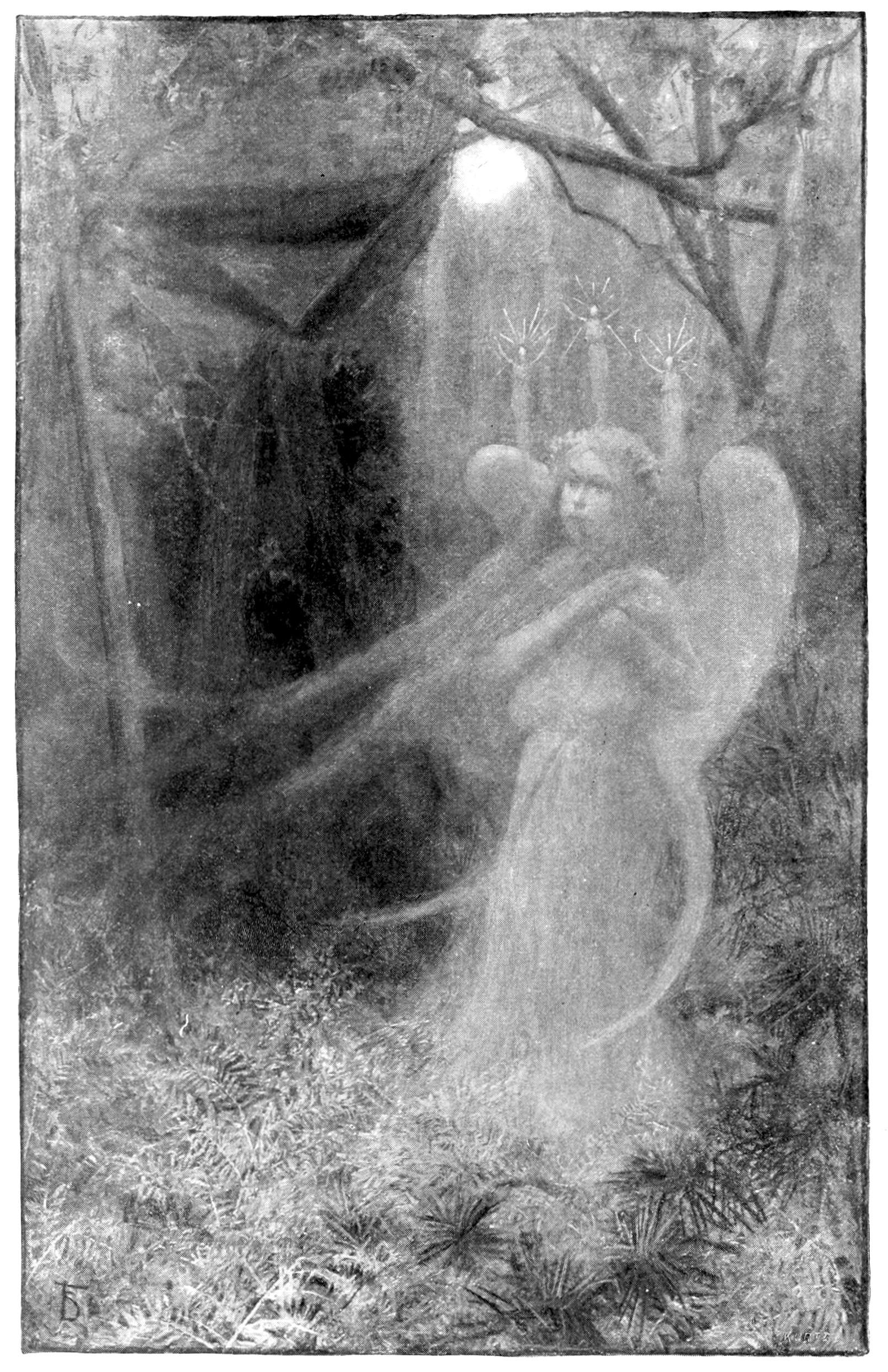

Louis Maurice Boutet de Monvel, Scène de la vie de Jeanne d’Arc, 1896

The garland of flowers & the crown of stars

“We are lost: we have burned a saint!”

— Words attributed to John Tressart, one of King Henry's own secretaries.

My dearest friend and fairy physicker, Lailoken, holds that there are many ways to be a “Gloaming Intercessor” (i.e, an envoy from the Otherworld, meant to act as a go-between, an emissary between this world and the other), and that the craft has many faces: working in the name of Christian spirits is one of these.

I am tempted to agree.

If anything, Joan of Arc deserves we hold respectful space for the contradictions in her story, which are not of her nature, but a fault to the limitations of our understanding of her.

It is true enough that Joan displays a number of highly meaningful signs and comes bearing a number of striking omens which I have repeatedly known and observed, in my own practice as a fairy intercessor, as rather intimately tied to Fairy and fairy-touched people or envoys - a manner of gender bending being the least of them. The accusations of witchcraft, heresy, idolatry, divination, and magic-working / spellcasting from Joan’s trial are rigged with implications and connotations when we replace them in the appropriate context of the eve of early modern France - lagged with symbolism, heavy with hidden meanings which the explicit discourse butchers. Importantly, the necessity for a fairy envoy to have been touched by the Others, initiated by Them, being “of” Them, in order to be granted permission to see and do in this world what They intend for them to see and do in this world, keeps coming back in Joan’s fairy history.

Indulge me, reader.

Bear with me.

Thinking, for a second, of Joan as a potential “persecuted changeling”, reframes the narrative of her trial in a completely new and somewhat compelling light.

We will not talk of seizures nor epilepsy, though the hypothesis has been raised before - see: fairy-stricken children, oh ! where does the soul go when it happens ?

“The use of fire in this case is very important as it is a common element in the stories concerning banishment of changelings. It is a method that pops up many times in the national folklore collection. Although in all the documented cases of changeling burning, [it] is the only one that involves an adult victim.”

— A. Bourke, The Burning of Bridget Cleary, 1999

(*shaking her head*)

There is, for instance, the strange case of Joan’s nativity - and I mean by that both in regards to what we know of her date of birth, and the stars which constellated the sky she was born under, according to Bernadette Brady’s parans delineations. Traces of fairy in the nativity is a niche interest of mine, and Joan’s natal chart is a fascinating case study - or, as my astrologer would say, always mind a busy 7th house.

Recently, I turned to Lailoken for help, asking for outside confirmation and validation on where I thought Joan was leading me, and had a divination done. Unbeknownst to me, and as we found out later on, together, I happen to have done so on the very date of Joan’s birthday - as good a sign and omen as any.

Joan was born in Lorraine, a territory culturally and historically disputed between France and Germany, on January 6th - the Twelfth Night. This is important as Joan was explicitly told by her spirits to “go to France”: French and Germanic folklore share a lot of interesting parallels when it comes to fairy beliefs, owing to the proximity of the countries and the territorial fluctuations happening in the mountainous regions of Eastern France, Southern Germany, Switzerland, and Northern Italy as a whole - a fertile land of stories and tales. Germanic folklore has it that, during the Epiphany, three mysterious women, fairy or goddesses (it is not always clear where comes one or the other), are said to travel across the land: three hooded figures, known as the Berchten. The Berchten are linked to the Rauhnacht festivals found across Germanic Europe such as in the Southern regions of Germany, Switzerland, and Austria. Similar to the Scandinavian Norns, this trio of sisters are also strikingly not unlike the Gaulish Matres, Materes or Matronae (the “Hooded Ones”, perhaps the Genii Cucullati). In Bavaria, the Berchten are believed to move through the villages, and this folklore seems spreaded out across the Alpine region, closely connected to the folklore of the goddess Berchta / Perchta / Bertha (from which the name Berchten derives) - a three-in-one “mother winter” figure, also said to be roaming the land during the days after Christmas up to the Epiphany, liminal days which belong to Her. Whether these figures are witches, goddesses, or fairies, depend largely on interpretation - but other European countries seem to draw identical conclusions, with local variances of course (Frau Holle in Germany, Holda in Austria, Perchta in Switzerland, La Befana in Italy, Berthe or Bertha in France, are but some examples of how this mysterious, potentially triple figure seems to appear). It has also been suspected that Berchta/Perchta, and her later incarnation as the Berchten, could be a surviving evidence of the Gaulish goddess Brixta, based on recovered archeological evidences from the Hallstatt period. Whatever the matter, in order to protect themselves from the Berchten, villagers south of Munich would write or engrave the letters “C+M+B+[year]” above their doors to guard the threshold and keep the fairy women at bay - the meaning of which generally understood to be “Christus Mansionem Benedicat”.

… However, other scholars point out that these initials could also be apotropaic Christian names given to the Berchten: none other than Catherine, Margaret, and Barbara.

Two of these ladies, we recall, Joan saw effectively, at the Fairy Tree of Domrémy: when They came to Joan near the fountain, she identified St Margaret and St Catherine, and was always adamant about her recognition.

It is thus Perchta who led me back to the Fairy Tree of Joan, as I was unearthing, under layers of ice and snow, clues of Perchta’s presence in the town I was born back home in France - when I was, in fact, seeking to connect with the Fairy Queen of the mountains, the one who wears the peaks on her brow, the one who is crowned in stars and makes edelweiss flowers rain from the sky like tears, falling - the one who tests the heart of the pure, drowns wicked towns under water, and will show her fair or foul face to you depending on which one you are deserving to know.

(As to who led me, first, to Perchta, I would be remiss not to thank my friend the magpie, Berta (@mascaberta) (yes…), who shared with me, in extreme generosity and confidence, a great deal of her own private research on the folklore above, particularly regarding the connexions of Berchta to the goddess Brixta, at a time where I was not so certain of what I was looking for. Berta prepares her own article on the topic, and once it is published, I will make sure to edit this one.)

Encouraged by Joan of Arc herself, under her tutelage and my interactions with her, I delved deep into the buried pre-Christian folklore that is linked to her date of birth - January 6th - and came full circle with this piece of lore. But to report back on my findings, we had, first, to consider which stories ought to be taken into account.

A word then, now, on Joan’s stars. An Acumen native, her heliacal rising star prophecies “suffering at the hands of others”, particularly in the case of attacks that weaken over time - the Thorn-Star (or so I have come to know Acumen) presiding over her destiny, fairy tree brambled with poison, gouging out the eyes of the impudent on its sharp, sword-like spikes. Joan, we have that in common - I see you. I witness. Stars explicitly connected with fairy-lore are also present in Joan’s nativity - precisely, the Ladies’ star, Alcyone (with Venus), the lore of the Pleiades speaking of many a fairy women, seven enchanted queens, seven hidden sisters, across various cultures. That one is obvious. Puzzling and strange is the co-presence of Polaris and Facies, stars which, in my own research on astrolatry as connected to the Good People, I have come to intimately associate with certain very particular class of the Pale Ones. And then… we find stars which indicate being obviously touched by the grace of the Otherworld - Vega, Orpheus’ lyre, enchanting human, stone, animal, death itself - that makes us pause, and reflect. Of course, we could address the more evidently difficult stars - such as Algol, the blinking one, sinister mother also known as the demon’s head, bestowing upon its native, so it was thought, a violent death. But I also wish to make honorary mention of two stars which I thought I would find in Joan’s chart, yet didn’t: Royal Star Aldebaran, the Knight of the Sky, and Bellatrix, the Amazon.

Not everything fits into one’s preconceived narrative.

(I say, staring at this rosary I just inherited from my grandmother - its small black pearls, its haloed Virgin resembling the Fairy Queen.)

Voices : An attempt at concluding

What is to be made of these striking parallels, of these complex overlayings of different faiths and practices ? Joan interpreted what she saw and heard based on her cultural understanding of things, which in turn informed her own spiritual understanding. Fulfilling a prophecy, creating it, like only true knights ever do, as she lived and quested, she met her spirit guides close to the fairy tree; and if not the fairy tree, then the fairy well - amongst these, two “ladies” - two maybe-saints - two saints - who do boast their own strong link to Fairy. There comes a time where we must remember, as practitioners, that research is water but never the fruit.

When I approached and asked Joan to show me whether to consider her a Fairy Saint would make sense, she answered, and facilitated even more research; even more contact with the right sort of people.

My friend Phro Nesis, deeply embroiled with her own Others, was kind enough to share with me what she has learned of Joan. Phro has long known Joan through the very lense Joan presented herself to me - as a venerable primogenitor of the French fairy resurgence or fairy reliance, and a common ancestor of the French fairy seers. Phro, having no doubts anymore, soothed my own by supplementing her UPG to mine, and I was shocked to hear how much and how far we had come to the same conclusions, independently, without concerting ourselves - for we did not know each other, then - simply by turning to Joan, speaking to her spirit, listening to what she had to say.

Interpreting, as it were, voices.

Through our own frame of reference - is it Truth ?

Phro later described how heathen the famous French “Fêtes Johanniques” (a celebration of Joan’s life and quest, following her path in the cities she crossed) become: where she lives, as the cortege passes, the procession is drawing from pagan as well as Christian memory, blending imagery, calling for a reconciliation of two faith’s respective wisdom.

If I rest my brown under the same tree, Joan, if I drink of the same well - then, what ?

Does it matter who speaks to me, who dances with me, what name “They” are called here and there, then and now ?

Does it matter to me, to you, or the inquisitor, the pyre ? Does it matter to history ? Does it matter to practice ?

In my experience, shared by Phro, Joan tends to present herself as a spirit emerging from the sovereignty of the French land - questions of the territory, of nobility, of royalty, even, coming to walk with her in her wake - and in this I recognize the Joan that came to me.

I understand, then why it would make sense for Joan to show me the way home to France when I arrive back, wearing my fairy rags, not knowing whether I still belong.

"Here begin the proceedings in matters of faith against a deceased woman, Joan, commonly known as the Maid."

— W. P. Barrett (trans.), The Trial of Joan of Arc (1932)

Was Joan of Arc a Fairy Saint ?

I don’t know - what do you think ?

(Yes. Yes, she was.)

George William Joy, Joan of Arc Asleep, 1895

Would you like to hear more ?

I presented my research on Joan of Arc as Saint of the French Fairy Faith as a Speaker at the Magickal Women Conference 2024 on Saturday, June 22nd (Birmingham, UK) - a 40 minutes lecture on the topic.

The incredible success of this talk led me to create a masterclass dedicated to Saint Joan of the Fairies or Jehanne-des-Fées, which I have made available both in French and in English. This course is comprised of a 1,5h lecture and its illustrated slide deck, and a workable “grimoire” of 80 pages to engage with Joan magically, The Book of the Maid.

The masterclass was pre-released on August 13th, 2024 to my Patreon members (who benefit from a 20% discount on this offering), and will make its official public debut on August 18th, 2024.

A permanent study group chat is open on my Patreon to engage with other students, and it would be my absolute pleasure to welcome you here with us, to talk all things relating to our unofficial “saint of the fairies”.

Selected Sources

W. P. Barrett, The Trial of Joan of Arc, 1932

https://sourcebooks.fordham.edu/basis/joanofarc-trial.aspA. Bourke, The Burning of Bridget Cleary, 1999

David Elliott, Voices: The Final Hours of Joan of Arc, 2019

Kathryn Harrison, Joan of Arc: A Life Transfigured, 2014

Andrew Lang, The Story of Joan of Arc, 1906

Andrea Martignogni, “‘Jeanne la Pucelle sous un grand arbre qui la fontaine ombrait’: L’arbre aux fées de Jeanne d’Arc entre pratiques sociales, rites et croyances à la fin du Moyen Âge”, 2012

H. Martin, Histoire de France, 1833

Thomas McGrath, “Fairy Faith and Changelings: The Burning of Bridget Cleary in 1895”, 1982

J. J. E. Roy, Histoire de Jeanne d’Arc dite La Pucelle d’Orléans, 1864

Edmund Spenser, The Faerie Queene, 1590

William Trask, Joan of Arc: In Her Own Words, 1996

Mark Twain, Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc, 1896

Marina Warner, Joan of Arc: The Image of Female Heroism, 2000