[EN] Twice-Born Brighid

A Seed of Sky-Fire from the Heifer and the Mare

Syncretic Theological Meditation of the Gallo-Irish Faith

This article was disclosed in exclusivity to my Patreons as part of their subscription’s privileges, granting advance access to any blog writing of mine ahead of its public release.

Please note, a complete French version of this article is available to read on my Patreon page. La version francaise de cet article est exclusivement disponible sur ma page Patreon.

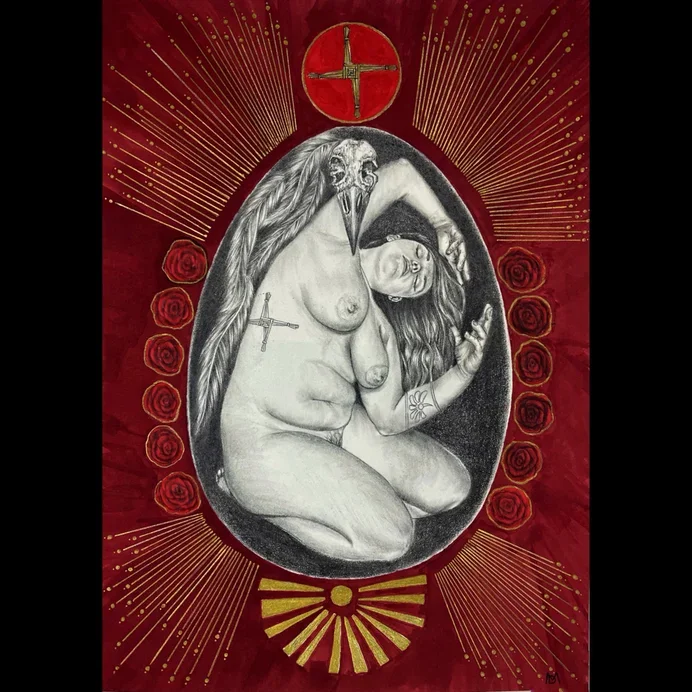

Trigger warning: sexually explicit image (the Dagda and the Morrigan’s coupling).

This short meditation article explores a deeply personal, syncretic theological reading of my tutelary goddess, Brighid, boldly positioning Her as a liminal fire-deity born of two maternal principles: the Morrígan, and Boann. Informed primarily by my own unverified personal gnosis (UPG), still I will be drawing from early Irish literature, academic sources and comparative Gaulish material as and where possible to present my theory, for in addition to a priestess I am, also, a scholar by trade and by love. Here, we will be arguing that, as daughter of the Thunderer with a matrilineal lineage of bovine and equine influence, Brighid emerges as a strong figure of sovereignty, encompassing notions of lustration and deep cosmological roots - fire born into water, lightning seeded into river and churned with milk. Be warned, then, than rather than reconstructing a singular “original” myth, this work embraces a living polytheist methodology that treats myth as a generative field rather than a closed archive.

Introduction: the First Fire at the Beginning of Man

While Her father is consistently named as the Dagda (the “Good God”, chief of the Tuatha Dé Danann), Brighid’s mother is never explicitly identified in the primary medieval sources. The identification of Brighid as the daughter of the Dagda is explicitly attested in Sanas Cormaic (Cormac’s Glossary), a 9th–10th century glossary traditionally attributed to Cormac mac Cuilennáin, king-bishop of Cashel:

“Brigit, that is, a poetess, daughter of the Dagda. This is Brigit the woman of poetry, whose sisters were Brigit the woman of healing and Brigit the woman of smithcraft. Therefore from her name all women poets were called brigit.”

— Sanas Cormaic, ed. & trans. Whitley Stokes and John O’Donovan, in Three Irish Glossaries (1862), p.23

In this entry on Brighid, the text is attributing to Her a triadic nature expressed through poetry, healing, and smithcraft: this is where of our modern understanding of the goddess emerges. While the Glossary reflects Christian-era redaction and tendencies, its preservation of Brighid’s divine lineage and threefold domain is generally regarded as drawing on pre-Christian learned tradition. This passage is among the earliest surviving textual witnesses to Brighid’s genealogy and functional triplicity, and it underlies much later medieval and contemporary interpretation of Her cult and functions – certainly, mine is based on this understanding.

However… the maternal lineage of Brighid is conspicuously absent from surviving Irish mythological texts - and this absence, I believe, is not neutral. Irish myth, as we know, preserved in manuscript culture, is fragmentary (some academic sources even talk about “Irish textual omelets”), Christian-mediated, and shaped by colonial epistemologies in which the gods were increasingly rendered as lesser legendary figures. Yet… Brighid Herself remains unmistakable, for She is fire. Not merely hearth-fire, but the first fire at the beginning of Man - that fire fallen from the sky, from the stars. Comparative evidence suggests She may even originally have been a dawn goddess, a bearer of celestial fire at the threshold of night and day. She is the fire that later translates as poetic illumination. In Gaulish contexts, Her cognate Brigantia appears associated with height, brightness, and possibly lightning as an inferred Daughter of a Thunderer / Sky-Father figure, often identified with Taranis. Indeed, if Brighid is daughter of the Dagda in Irish tradition, and Brigantia daughter of a Thunder-God Dis Pater in Gaulish contexts, the comparative convergence is striking, and quite irresistible besides: She is fire descending from sky into world. Brighid thus becomes a seed of lightning, dropped, as we shall see, into river water, born where night meets day.

But then again: who is Brighid’s mother ?

Over the years, I have asked myself this question countless times - as a devotee, a researcher, and a theologian. In the answers I found, and the practices I developed with consistency, meaning, and purpose, I’d like to propose that Brighid could be read as born of two mothers – this, mind you, not as a literal genealogical claim, but as a theological articulation of Her liminal nature: fire held between sovereignty and sustenance, blood and milk, war and healing.

I do openly embraces syncretism as a methodological choice: I am a Gallo-Irish Polytheist, so please keep this in mind, for I do have my own bias ;) In living polytheist traditions, syncretism is not corruption, but continuity: a recognition that gods travel, transform, and speak through multiple cultures, masks, and times. This voyage is not always one from polytheism to monotheism: sometimes, like in this case, it comes from the Continent to the Isles.

First Mother: The Morrígan and the Horse’s Might

This identification is explicitly UPG: it arose organically from mythic structure rather than invention ex nihilo.

In the Cath Maige Tuired (The Second Battle of Mag Tuired) the Dagda couples with the Morrígan on Samhain’s Eve above a river, a hierogamic act that confers sovereignty and victory upon the Tuatha Dé Danann in a time of great need at war:

“The Unish of Connacht calls by the south. The woman was at the Unish of Corand washing her genitals, one of her two feet by Allod Echae, that is Echumech, by water at the south, her other by Loscondoib, by water at the north. Nine plaits of hair undone upon her head. The Dagda speaks to her and they make a union. Laying down of the married couple was the name of that place from then. She is the Morrigan, the woman mentioned particularly here.”

— Cath Maige Tuired, translation by Morgan Daimler

The traditional medieval Irish narrative has the Morrígan standing with one foot on each bank of the River Unius (Unshin) when the Dagda enters her. This river is located in Connacht and has been associated in later tradition with an area near Riverstown in County Sligo, though exact identification with a modern Irish river is rather… uncertain. At this point, I must acknowledge that I followed myself onto something of a tangent. Having posited the river of Cath Maige Tuired as the Unius, I wondered whether it might constitute a branch of the river Shannon, whose mythic and cosmological weight would further deepen this reading. The Shannon, in the Auraicept na n-Éces (The Scholars’ Primer - an early medieval Irish scholarly treatise that presents Ogham as a divinely inspired, cosmological, and linguistically ordered system, preserving its origin myths, literary theory, and sacral intellectual framework) is associated with the letter Luis, itself a letter frequently linked to Brighid in later esoteric and devotional traditions. Luis carries a cluster of symbolic bríatharogaim (“word-oghams”) concerned with healing herbs and the brightness of flame, reinforcing Brighid’s dual identity as healer and fire-bearer. If the Unius had flowed into the Shannon, I thought, this might have suggested a continuous mythic current… Geographically, however, this connection does not hold: the Unius belongs to a different watershed. Yet the impulse behind the question remained instructive, insofar as Irish rivers are concerned, and as we shall soon explore, for it reveals the way mythic logic often follows symbolic and cosmological associations rather than strict hydrology, tracing correspondences between rivers, letters, and divine powers even where the land itself draws firmer boundaries.

The mating scene of these two powerful deities is dense with symbolic charge, bridging liminality, prophecy, sexual union, and water as a medium of power. The Morrígan, after the coupling, washes her genitals in the river in an act that binds sexuality and prophecy to flowing water: the seed of the thunder-god, from the matrix of Her womb, then drops into the river. In this reading, Brighid quite literally becomes Fire-in-Water… and the paradoxical convergence of purification with, broadly speaking, danger (where it pertains to a mother-goddess of many battles, capable of granting and withdrawing the favour of Fate).

When it comes to the gods… we have seen stranger births.

It feels important to repeat again that the Morrígan is not merely the carrion crow “war goddess”: in the myths, She is a sovereignty figure, a chooser of kings, and a fate-looming presence who moves between land, battlefield, and Otherworld. She is also associated with horses - most notably through the figure of Macha, who claims kingship through a deadly horse-race while pregnant, and births two twin foals in Her ordeal. Horse symbolism throughout a broader Indo-European context is tightly bound to sovereignty, kingship, and sacrificial legitimacy: Macha and the Morrígan ride the liminal currents of power, Their presence inseparable from that of the pregnant mare. This divine she-horse is more than a mount: She is an extension of Their essence, a conduit of strength, frenzy, and foresight. In battle and ritual, Her hooves strike the earth as a drumbeat of authority, Her mane a banner of unbridled power. Through Macha and the Morrígan, the horse embodies both chaos and order, ferocity and might, a living symbol of power that flows between the human and the divine. To engage with this face of the goddess is to witness the union of warrior, deity, motherhood and beast, a complex through which the world is claimed, transformed, and renewed.

Imagining Brighid as daughter of the Morrígan is to recognise, possibly born there and then, Their shared grammar of fire and blood, and, importantly, the dual capacity to heal and to harm, to cauterize and to destroy. Fire is not gentle by default. It knows transformation, poison as medicine, and medicine as poison.

And so here is the first mother.

The Second Mother: White Boann at the Cow’s Flank

Now then… What is a river, if not water snaking its way through the terrain ?

We established that the river of Cath Maige Tuired is not named as the Boyne, yet as I alluded prior, in Irish cosmology rivers are certainly not isolated systems. All rivers ultimately go back to the primordial ocean, and mythically, flow into the Boyne itself - the great river of knowledge and origin. Boann, its goddess, is a figure of transgressive wisdom: she approaches the forbidden well, is wounded by its waters, and then turns into the river itself, being carried away to the great salt sea. She is also repeatedly associated with the white heifer, and that is no coincidence, either.

In mythography, rivers are often conceived as life-giving, flowing embodiments of divine power, while cows, particularly white cows, function as conduits of nourishment. Boann or Bóinn, as river goddess of the Boyne, is both river and cow, and in Irish literature She indeed embodies both forms: Her river carries the vitality of the land, while Her bovine aspect provides the milk that sustains life and confers spiritual blessing. Early Irish mythology frequently links rivers and cows as symbols of fertility, abundance, and sovereignty - we know: so many cattle raids… White cows, particularly those marked with red ears, are Otherworldly beings whose milk conveys sustenance and divine blessing.

Scholars have also noted an important celestial correspondence: the Milky Way is described as a “river of milk,” suggesting a cosmological reading in which terrestrial waters mirror the stars and encapsulating the deep symbolic resonance of cattle and waterways in the heavens as well as on the land. Known in Irish as Bealach na Bó Finne, literally “the Way of the White Cow”, the Milky Way bears a name that invokes both the celestial river of stars and the sacred river on land. This parallel casts the visible band of the Milky Way as a luminous cosmic river of milk, echoing terrestrial waters that nourish body and land, and situating the White Cow as a liminal creature at the threshold between earth and sky. Through this lens, heifers and rivers co‑extend from the landscape of myth into the very structure of the land and sky, reflecting a worldview in which fertility, sovereignty, and sacred flow are inseparable from the constellations that arch above them – a vivid, starry cosmogony. More contemporary studies of Irish archeoastronomy further reinforce the symbolic nexus of cattle, rivers, and the heavens. In Island of the Setting Sun: In Search of Ireland’s Ancient Astronomers, Anthony Murphy and Richard Moore argue that the builders of the Boyne Valley megalithic monuments designed their monuments with an integrated sky–land cosmology, in which the Milky Way and its stellar patterns were as meaningful as solar and lunar cycles. The authors suggest that ancient builders saw the Boyne River and its sacred landscape as part of a terrestrial reflection of the celestial river, with its alignments and quartz facades echoing the band of stars bisecting the night sky. They propose that the Boyne Valley’s sacred sites, including Newgrange and its counterparts, functioned within a sophisticated integration of landscape, celestial observation, and mythic memory. Thus Boann becomes not merely a river goddess, but a cosmic lactating mother, Her milk the flow of stars and their light.

In this way, Brighid’s second mother, a river, the River, is simultaneously river and cow, terrestrial and celestial, nourishing both the body and the spirit. Brighid as daughter of the White Cow is fire born of water and churned into milk, hearth-flame fed by subsance, inspiration nourished by abundance. Milk, like water, is a carrier of life and cosmic order.

And there is the Second (foster ?) Mother.

Early hagiography of Saint Brigid and later vernacular tradition preserves a striking residue of this symbolism: the saint is said to have been fostered by a red-eared white cow - a classic marker of fairy cattle in Irish tradition, originating not from the human realm but from the síd. Such details are rarely incidental ! The red-eared white cow that nurses Saint Brigid marks her nourishment as otherworldly, with milk drawn not merely from an animal, but from the land’s hidden sovereignty. Such animals frequently appear as gifts, guardians, or nourisher figures in myth and folktale, and their presence signals divine favour, liminality, marked Other-ness or supernatural origin. A Chrsitian saint fostered by fairy cattle ? Come one now. The motif is, of course, especially significant in the case of Brighid the goddess. That Saint Brigid is sustained by a fairy heifer situates her nourishment firmly outside ordinary human economy. The persistence of this image within Christian hagiography cannot be simple folkloric embellishment, in my opnion, but suggests instead a deliberate preservation of older theological memory beneath a saintly veneer, linking the saint to earlier conceptions of Brighid-as-goddess.

The cow’s milk, in this context, functions not merely as sustenance but as a medium of divine or at the very least otherwordly transmission, from those invisible we share the world with.

Cow and Horse: The Sovereign Elixir

One mother a mare, the other a heifer.

Cows and horses dominate Irish heroic literature because they dominate Irish sovereignty economics. To possess cattle was to possess wealth. To possess horses was to possess kingship and military power. Cattle raids such as the Táin Bó Cúailnge are not mere adventure tales but mythic dramatisations of sovereignty struggles.

The Morrígan (through Macha in particular) and Boann together embody twin poles: horse and cow, blood and milk, war and nourishment. And Brighid, as Their daughter, would stand precisely at this intersection. Her domains (healing, poetry, smithcraft) are all technologies of civilisation, requiring both raw force and careful sustenance.

Cattle in early Irish society were not merely economic assets but embodiments of sovereignty, legitimacy, and the land’s blessing. Milk, as their product, functioned as a sacral substance, conferring nourishment, health, and right order: that one is obvious. But, in addition to milk and other milk produce such as cream or butter as symbolic substances associated with the heifer and the land’s nourishment, another sacred liquid aligns on the other hand with the symbolism of the horse and the granting of sovereignty: honey and the fermented elixir made from it, mead.

In early Celtic contexts, mead is more than a luxury beverage of kings: it is the holy ritual drink tied to their intronisation, power and rightful rule. The queen or sovereignty goddess, by offering Her cup of mead to a king, was understood to bestow legitimacy and lordship upon him, integrating communal and supernatural orders. This association is mirrored in the etymology and mythic role of the Irish sovereignty figure Medb, whose name is linked to the Proto-Celtic root medu- (“mead”) or medua (“intoxicating”). In myth, such figures embody both the intoxicating allure of power and the sacred rite of investiture, offering the drink of sovereignty to those chosen to rule by Otherworldly powers in right order. The horse, a rare mark of status and wealth in early Irish society, complements this sacred drink. Horses appear in multiple goddess cycles from Rhiannon to Epona, with remarkable consistency, often associated with fertility, warfare, and kingship, and thus resonating with the sovereignty cup’s sacred purview. As such, while the cow’s milk and its derivative signify sustenance, nourishment, and the material blessing of the land, honey and mead, offered alongside a horse figure, signify the intoxicating gift of sovereignty, prophetic speech, and the ritual bond between worldly and otherworldly power.

Within this interval on sacred drinks and nectars, the Indo-European image of a great serpent (remember how all rivers are serpents or dragons ?) churning cosmological waters offers a potent cosmological grammar through which Brighid’s role may be further articulated - for She is also, Herself, a goddess of brewing. In multiple Indo-European and comparative mythic systems, primordial elixirs are not simply discovered but produced often through violent, liminal motion: water is agitated, heated, boiled and transmuted. This process is frequently imagined as the work of a Great Serpent thrashing in the primordial sea or ocean, using the world-axis or a mountain (remember: Brighid’s name comes from a root-word meaning high, or exalted, and in Gaul, Her cognate Brigantia is associated with high places and peaks for this very reason) as a churning rod. Under the serpent’s movement, water becomes fiery, boiling, foaming (we come back easily to the mysteries of Fire-in-Water here), and is then transformed into… milk. Read through this lens, Brighid’s association with the serpent, preserved in folk tradition, healing charms, and Imbolc imagery (in particular in Scotland), positions Her not just as guardian of fire or milk, but as mistress of their transmutation. The serpent’s churning renders water into milk just as Brighid’s fire renders milk into butter, poison into medicine, chaos into order. From one tip of Her fingers, She melts the ICE and wakes the land from its wintery slumber. She stands at the threshold where water is no longer only water, and fire is no longer only flame, but where both become sacral substances capable of carrying divine presence.

The Economics of Lustration: Where Fire Clarifies

Fire is the highest form of purification - because it is absolute. Brighid’s well-known triad, Fire in the Head (inspiration), Fire in the Heart (healing), and Fire in the Hands (craft), collapses the boundary between inner and outer worlds. There is no sharp division between the human and the divine here. Fire passes between them freely. In this light, fire naturally occupies a central place within temples and nemeta, just as water does. Both are maintained there not merely as symbolic elements, but as agents of passage. Fire, through its verticality and its power to consume, and water, through its depth and continuity, each open (in their own way) a point of contact with the Otherworld: the one through elevation and clarity, the other through immersion and memory. Their ritual co-presence in sacred places creates a liminal space in which the boundary between the visible and the invisible grows thin, allowing the circulation of influences, utterances, and powers. Mist, born of their meeting, completes this triad of passage: neither fire nor water, but the veil through which the many so-called “Celtic Otherworlds” are most often accessed. When fire and water meet, mist arises as the soft threshold through which otherworldly denizens may draw near.

Across Indo-European ritual systems, the ritual purification of the warrior is an important rite - hygienic and moral, of course, but of cosmological importance also. In this specific ritual, this complex of symbols is expressed through the combination of the sovereign and nurturing powers of the horse and the cow. The warrior, having crossed into states of sanctioned violence, bloodshed, and liminality, must be ritually re-integrated into social and sacral order. In Insular and Continental Celtic contexts, this reintegration appears to have been enacted through a sequence of elemental rites involving water, fire, milk, and butter, a ritual grammar that resonates strongly with Brighid’s domains and functions.

Water is the primary agent of purification, a reality that persists even in our daily lives and ablutions, composed of countless washings and rinsings. Rivers, wells, and boundary waters function as liminal membranes through which the warrior passes, shedding the excess of battle-fury and re-entering communal time. Irish literature preserves repeated associations between warriors and ritual bathing, often in heated or magically charged waters, suggesting not only cleansing but transformation. Fire follows water, not as its opposite, but as its intensification. It purifies by truth, by reduction, by revealing what endures.

Milk and other milk produce, with butter in particular, introduce a third and crucial register. Unlike water and fire, milk is explicitly maternal, tied to nourishment as a tool of social continuity. To drink milk is to partake in the land’s blessing. Butter, as transformed milk, carries this symbolism further: it is cultivated abundance, wealth stabilised through human care. The use of milk and butter in purification rites suggests that the warrior is not only cleansed of violence, but re-adopted by the land and the tribe.

As argued above, Brighid’s fire is not destructive by default, but lustral, capable of cauterizing wounds, sealing breaches between worlds, and restoring right order. In this context, fire functions as the warrior’s second threshold: having been washed, they are then re-forged. Here, the presence of Brighid as White Cow’s daughter becomes especially salient. Milk cools what fire has tempered, butter seals what water has washed. Together, these substances restore the warrior to hearth and kin. This ritual sequence, theologically grounded reconstruction rather than a directly attested ritual formula, can thus be read as a movement from liminality back into sovereignty, from bloodshed into blessing. It encodes a theology in which violence is neither denied nor glorified, but ritually metabolised. Brighid presides over this process not as a passive healer, but as a sovereign flame who understands that to heal is to harm and to harm is to heal.

Conclusion: From Dawn to Twilight

Brighid emerges, in my own UPG, as born in the twilight (or dawn ?) between opposites: between rivers and stars, land and sky, between fire and water, heifer and mare, blood and milk, healing and harming, chaos and order. She is the spark that travels through the serpent’s churning waters, the flame that transforms milk into sacred substance, the fire that re-forges the warrior and nurtures the land. As daughter of two mothers, one martial, one nourishing, She embodies a polyvalent and complete sovereignty, teaching that power, sustenance, and transformation are inseparable. To engage with Her is to witness the cosmos in motion: rivers flowing into the sea, milk flowing into butter, water and fire dancing across thresholds. Brighid’s gift is the alchemy of liminality: She makes the mortal sacred, the dangerous nourishing, the chaotic ordered, and in so doing, invites us to carry Her fire as active participant rather than kneeling witnesses. In recognising Her, we do not merely study myth: we kindle Her very fire, preserved in it.

I recognise She of the White Palms

in the rising light of the winter sun

in the fire-seed of sky-father

in the womb-waters of war-mother

in the foamy milk of river-mother

I recognise Her in the white of milk and the gold of mead and honey,

suckling at the udder of inspiration

in the prophetic sting of the bee,

in the red of the furnace.

I recognise Her in the fire She imparted to me –

fire in the head, fire in the heart, fire in the hands.

She the red-eared white cow.

I recognise Her in the miracles I work.

I recognise Her in the green of the land.

I recognise Her in the safety of the hearth.

I recognise Her in the burning fever cooled by gentle hands.

I recognise Her in blossoming trees.

I recognise Her in the body warmth of my lover’s skin.

I recognise Her in the Snake that coils within, without.

I recognise Her in the cauterizing edge of the blade.

I recognise Her in the principle that

sometimes to heal is to harm and to harm is to heal.

I recognise Her in the salt of mourning tears.

I recognise Her when She takes me Home –

and I say Her name.

Selected Sources & Further Reading

Bitel, Lisa M. Landscape with Two Saints: How Genovefa of Paris and Brigit of Kildare Built Christianity in Barbarian Europe. Oxford University Press, 2009.

Carmody, J. Auraicept na n-Éces, 1917 critical edition.

Carey, John. A Single Ray of the Sun: Religious Speculation in Early Ireland. Andrias Press, 1999.

— The Irish National Origin-Lore. Dublin, 1994.

— “The Morrígan as Sovereignty Goddess.” Ériu 37 (1984).

Carmichael, Alexander. Carmina Gadelica: Hymns and Incantations. Edinburgh, 1900–1971.

Cogitosus. Vita Sanctae Brigidae. 7th century. (Trans. Richard Sharpe, Medieval Irish Saints’ Lives, 1991.)

Daimler, Morgan. Cath Maige Tuired: A Full English Translation, Kindle, 2020.

— Brigid: Meeting the Celtic Goddess of Poetry, Forge, and Healing Well, Pagan Portals, Moon Books, 2016.

DuBois, Page. A Million and One Gods: The Persistence of Polytheism. Harvard University Press, 2014.

Dumézil, Georges. Mythes et dieux des Indo-Européens. Flammarion, 1992.

Eliade, Mircea. Rites and Symbols of Initiation. Harper & Row, 1958.

— The Myth of the Eternal Return. Princeton, 1971.

Green, Miranda. Symbol and Image in Celtic Religious Art. Routledge, 1992.

— The World of the Druids. Thames & Hudson, 1997.

Harvey, Graham. Celtic Goddesses: Warriors, Virgins and Mothers. 2002.

— Listening People, Speaking Earth. Hurst, 2005.

Heesterman, J. C. The Inner Conflict of Tradition: Essays in Indian Ritual. University of Chicago Press, 1985.

Lincoln, Bruce. Death, War, and Sacrifice. University of Chicago Press, 1991.

Mac Cana, Proinsias. Celtic Mythology. Hamlyn, 1970.

McCone, Kim. Pagan Past and Christian Present in Early Irish Literature. Maynooth, 1990.

Murphy, Anthony & Moore, Richard. Island of the Setting Sun: In Search of Ireland’s Ancient Astronomers. Dublin: Liffey Press, 2006 (2020 revised edition).

O’Rahilly, T. F. Early Irish History and Mythology. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, 1946.

Ó Catháin, Séamas. The Festival of Brigit. DBA, 1995.

Ravenna, Morpheus. The Book of the Great Queen: The Many Faces of the Morrígan from Ancient Legends to Modern Devotions. Concrescent Press, 2015.

Whitley Stokes & John O’Donovan, Sanas Cormaic, ed. & trans. in Three Irish Glossaries (1862), p. 23.

York, Michael. Pagan Theology: Paganism as a World Religion. NYU Press, 2003.

Zimmer, Heinrich. Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization. Princeton, 1946.